Artificial intelligence (AI) enabled tactics, techniques and procedures have been framed in contemporary cyber conflict discourse as a driver for a new swathe of threats, ranging from rapidly generated disinformation content to highly refined malware. This essay argues that, while this may be true in future, such narrative framings of AI are largely driven by hype, and that excitement about the potential threats of AI use by threat actors does not map up to the use cases presented in literature. At present, threat reports emerging by the private sector – specifically, owners and operators of AI models – demonstrate that AI is being used by state-backed threat actors, but not that AI use leads to a commensurate increase in efficacy or effectiveness of operations or products. Failing to account for hype in relation to AI is thus our largest blind spot in understanding cyber conflict. Ignoring hype – particularly in the context of how governments understand and are involved in cyber conflict – can lead to a misallocation of resources, and a misunderstanding of the solutions required to counter AI-enabled threat actors. Indeed, it may not even be useful to distinguish between threat actors using AI, and those not.

What do We Mean by “Hype”?

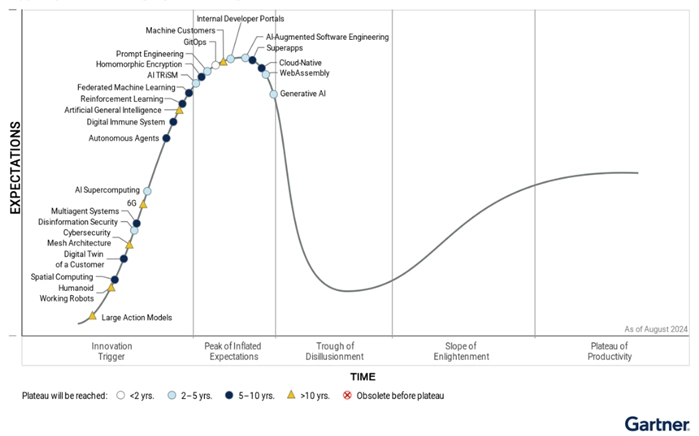

Mismatches between perception and reality are a fundamental characteristic of cyber conflict policy conversations. That is, the mundane reality of protecting infrastructure and systems as part of a wider conflict rarely maps up with the imaginaries and excitement that encircle the contemporary warfighter. “Hype”, however, is a distinct form of structured excitement outlined by Gartner as possessing five stages of a “hype cycle” outlined in Figure 1 below.

Gartner’s hype cycle identifies how, following an innovation being triggered, expectations become dramatically inflated, collapse in a “trough of disillusionment” before increasing again as technology implementation increases in productive ways – but never to the point of the peak of inflated expectations.

While the hype cycle with regard to generative AI has peaked, meaningful applications remain 2-5 years off – and will likely not map up with the reality presented. This reflects narratives relating to hype and cybersecurity more broadly, with hyperbolic discussion of “cyber war” based on misunderstandings of bugs in industrial control systems or insufficient server space being purchased undermining serious discussions of legitimate attacks by malign actors. Robert M. Lee and Thomas Rid, in their identification of thirteen reasons why hype makes for bad cybersecurity policy, identified that hype clouds sound analysis of risk, undermines trust in the Internet and warps priorities for potential security or regulatory interventions.

In the case of AI in the cybersecurity context, Rid’s assertion that “cyber war will not take place” is regularly jettisoned when a change in technological paradigm occurs. AI is no different, with one Indo-Pacific cybersecurity vendor arguing that Chinese-developed open-source AI model Deepseek had the power to “elevate the Chinese Communist Party as a gatekeeper to history and knowledge itself” – an argument drawn from the factual reporting of the Deepseek model’s censorship of anti-PRC content such as the Tiananmen Square Massacre, but hyperbolised to argue that the mere existence of the model was an existential risk.

Hype in Threat Reports

While it has been noted that hype leads to bad policy development and outcomes, the general excitement surrounding AI has led to it being incorporated into threat reports and analysis from government as a unique driver of cyber conflict and risk. The mere existence of AI models is argued to be an accelerator of effective cybercrime business models, highly refined critical infrastructure and the death of truth within government cyber policy documentation.

Threat reports from AI vendors and developers such as OpenAI, for example, identify the use of their models for malicious purposes including the development of disinformation content for use in influence operations, and refining malware to attack Western liberal democracies. While they identify and take steps to attribute these malicious uses of AI, what the reports lack any accounting of is whether such products developed with AI assistance have the intended effect, or any effect at all. Yet such reports present AI as the prime determinant and driver of disinformation and malware – a problem shared with studies of disinformation in general, which often conflate the functional truth that humans lie with the internet and digital technologies having somehow made those lies more effective. Similarly, AI’s impact on elections was overemphasised, distracting from functional realities of “disinformation” being spread through legitimate channels such as podcasts by human actors.

At present, institutional knowledge generated from UK and European Union cybersecurity policymakers fails to identify the distinction between the increased availability of AI tools, and a purported increase in effectiveness of AI-generated or assisted content. Both the UK National Cyber Security Centre and, more recently, the UK’s AI policy regime have mentioned a supposed universal acceleration capability for AI to spread new, improved forms of disinformation. ENISA documentation identifies the possibility of “new avenues for manipulation and attack methods”. By contrast, the EU’s framework for regulating AI systems used in cybersecurity under Article 15 of the EU AI Act has clear requirements for owners and vendors to manage clear risks in their systems. While it certain accelerates the production of content, whether that content is of improved effectiveness is not addressed or proven.

In the Absence of Hype…

This discussion is not to say that AI tooling is not useful in the context of cyber conflict; AI tools such as Microsoft Security Copilot have potential to reduce errors, burnout and administrative overheads for staff in security operations centres through mapping incidents to MITRE ATT&CK controls and assisting in report writing. AI does present opportunities to improve detection and triage of attacks, and automating low-end taskings that would otherwise exhaust junior analysts.

Nor is it to say that AI tools are completely without risk, particularly where surveillance and exfiltration of data is concerned. In the case of DeepSeek, wherein the application has already been banned from Australia, South Korean and Taiwanese government devices, risk is known and can be controlled for by end users. This is in much the same way as controls on TikTok being used on government devices; where a threat is present and known, hype moderates down to the “slope of enlightenment” outlined in the Gartner framework. Where the potential risk is unknown, hype appears to be more pointed. In the final week of January 2025, the contrast between Google Threat Intelligence Group’s reporting on threat actors utilising the Gemini LLM for slight productivity gains for vulnerability research and automating workflows and reports about DeepSeek functioning as a means for one government to control the truth itself.

In summary, it's clear that hype about AI is a major blind spot for our understanding of cyber conflict. Hype fundamentally relates to a misunderstanding of risk and produces a misallocation of resources. Baking hype-based misunderstandings of AI’s capabilities into policy responses to cybersecurity may produce strategies and workforces built on protecting against the implausible and ignoring the possible.